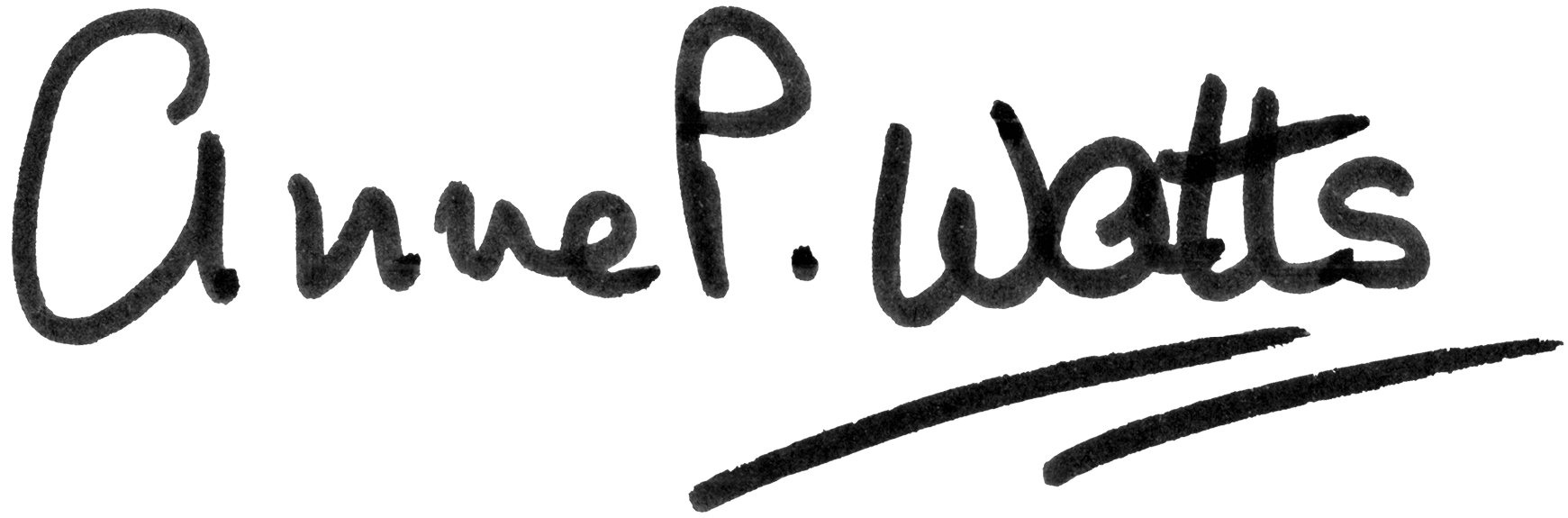

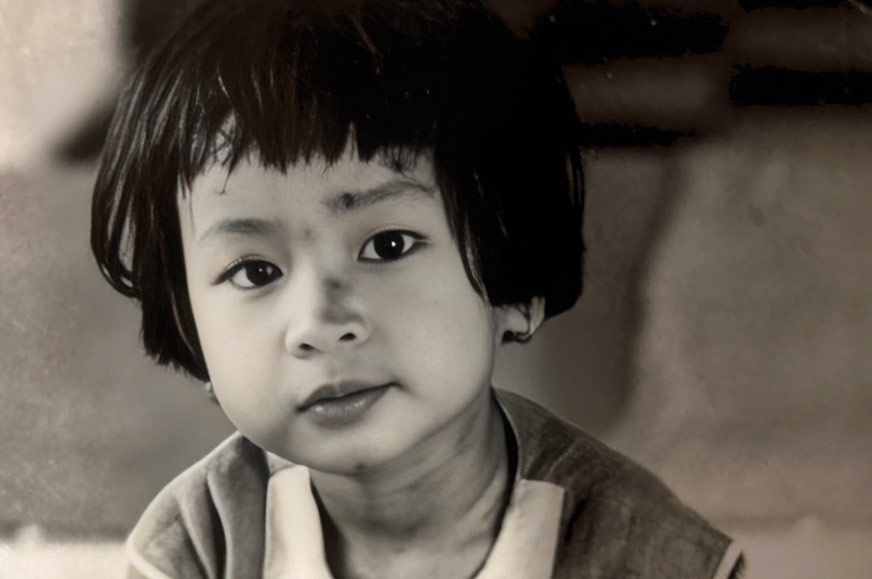

Sa Keao, October 1979 – December 1980. Picture this, 41,000 displaced Cambodian people fleeing across the border into Thailand.

Nothing but the clothes on their backs. Following 4 years of a brutal regime under the Khmer Rouge which had created a hell where some 1.7 million people died of torture, disease and famine. Over a few weeks, many more thousands flooded into Thailand.

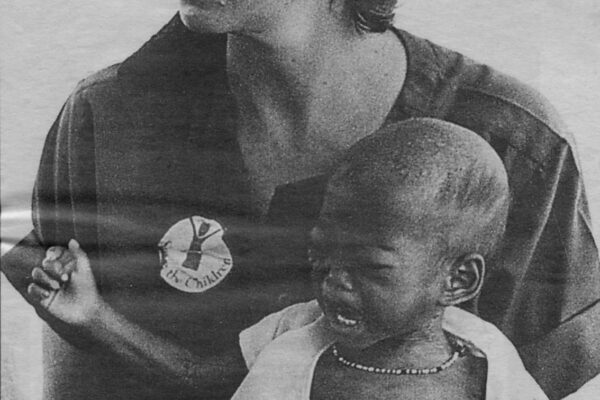

Ideally, a camp is put together before 1000s of people flood in. Latrines have to be dug; safe drinking water has to be sourced, transported and distributed; shelter is required to protect people from the elements; a hospital area needs to be functioning to take the sick, wounded and traumatised with clinics to support mothers and their children suffering from those illnesses common in the dispossessed. Medical supplies, equipment and food have to be transported stored securely and distributed fairly. Effective and plentiful manpower to make all this happen quickly is essential and usually involves military personnel. Medical teams arriving that October 1979 did not have the luxury of time.

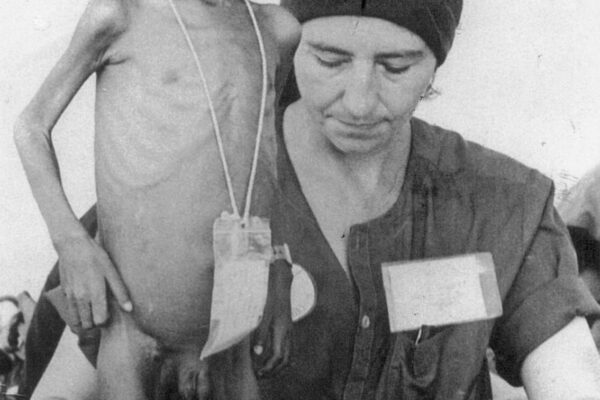

The sight that met me on that October day stunned me. I stood in my crisp, white nurses uniform trying to process what I was seeing. Ahead of me was a mass of blackness as far as the eye could see. As my senses adjusted I realised with horror that the mass ahead were people, 1,000s lying on the ground clad in ragged black pyjamas like clothing. What struck me then and stays with me now was the silence; no babies crying; no one coughing; no weeping; no laughter. The stench was overpowering.

Tears prickled my eyes and anger flared at this manmade catastrophe ending in such human degradation. I wanted to turn and run but my nurse training kicked in, took over and a calmness returned.

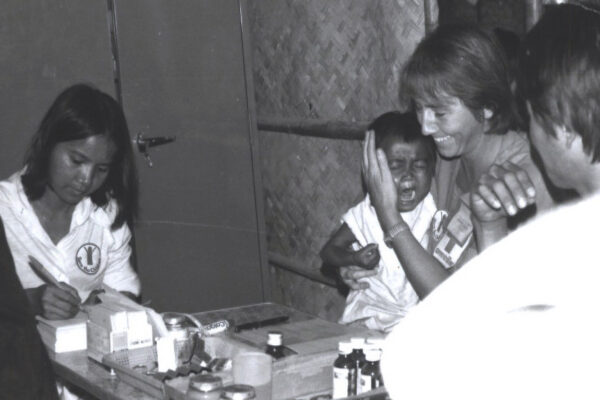

Over the next 10 days as medical teams arrived; the bamboo and thatch camp was constructed; the weakest died and were buried; the UNHCR, ICRC, MSF, the Thai Military and the Thai Red Cross quickly restored order from chaos.

On the 10th day some 39,000 displaced Cambodians moved in and the process of managing this human tragedy could begin to be unravelled. Life in camp moved on; kites flew; children laughed; people talked; hearts lifted.

While nurses, doctors, nutritionists and volunteers can work miracles, the ultimate tragedy is that these miracles are restricted by the rigid framework of whatever the prevailing political situation is.